Alzheimer's disease is characterized by a progressive decline in cognitive abilities, including memory, thinking, and behavior. Symptoms often start with mild cognitive impairment, but worsen over time, impacting activities of daily life. Ultimately it results in physical impairments as well. While memory loss is a hallmark symptom, changes in mood, paranoia, disorientation, and difficulty completing familiar tasks also commonly occur.

In this issue of Synapticure on Science, we’ll share the following information about the Alzheimer’s epidemic affecting millions of Americans and how Synapticure can help support you and your family.

- Statistics about the rising incidence, prevalence and mortality of Alzheimer's

- Alzheimer’s risk factors: age, genetics, gender, military service and lifestyle

- The importance of timely dementia diagnoses and partnerships with primary care physicians

The Prevalence of Alzheimer's Disease

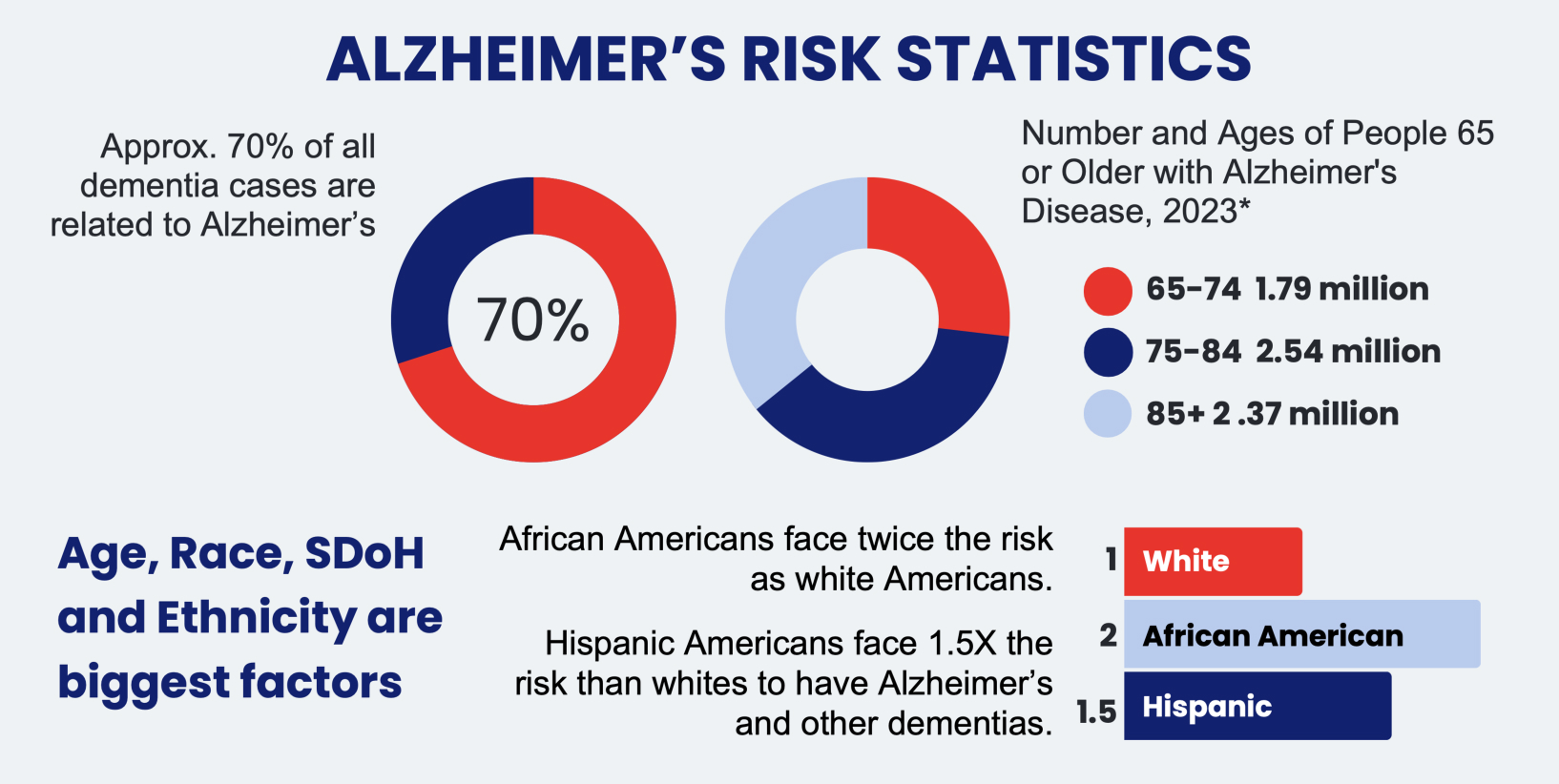

Alzheimer's disease is a significant health concern in the US. According to the Alzheimer's Association 2023 Facts & Figures Report, approximately 6.7 million Americans aged 65+ are currently living with Alzheimer's. The breakdown is as follows:

- 1.79 million (27%) = 65-74 years old

- 2.54 million (38%) = 75-84 years old

- 2.37 million (35%) = 85+ years old

Additionally, an estimated 200,000 people under 65 are diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer's.

In the US alone, someone develops Alzheimer’s every 65 seconds. The number of people affected by Alzheimer’s is skyrocketing. According to a recent Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study published in The Lancet Public Health, the number of people aged 40+ living with dementia is estimated to nearly triple by 2050, with its global prevalence projected to rise to 153 million people. In the US, every decade brings an ominous forecasted increase in the prevalence of Alzheimer's, with 8.4 million by 2030, and 11.6 million by 2040, ultimately impacting 14 million people and their families by 2050.

Alzheimer’s Mortality

We lose nearly 120,000 Americans each year to Alzheimer’s, making it the seventh leading cause of death in the United States. Comparatively, although deaths from heart disease have decreased by 14% since 2000, deaths from Alzheimer’s disease have increased by nearly 90%. Indeed, 1 out of 3 senior citizens dies with Alzheimer’s or another type of dementia.

From the time of diagnosis, people with Alzheimer’s disease usually have about 3 to 11 years to live. However, some people live beyond 20 years from diagnosis.

According to the CDC’s 2021 data, the Alzheimer’s mortality rate differs widely across the US. The states with the highest mortality rates are: Mississippi (52.8%), Alabama (46.8%), Washington (45.5%), Georgia (44.5%), and Arkansas (43.2%). Those with the lowest rates are: New Jersey (20.6%), Florida (19.6%), Massachusetts (17.7%), Maryland (16.1%)—and New York (13.6%), which has the lowest mortality nationally. Where does your state rank?

Risk Factor: Age

While several risk factors contribute to the development of Alzheimer's, the greatest risk factor for Alzheimer's disease is age: the older you are, the more likely you are to develop the disease. Among Americans over 65, following is the proportion of people living with Alzheimer’s:

- 5.0% of people age 65 to 74

- 13.1% of people age 75 to 84

- 33.2% of people age 85 and older

This translates to 1 in 9 people over the age of 65 who are affected by Alzheimer’s.

Risk Factor: Lifestyle

While some factors are beyond our control—like age, gender and genetics—one risk we can control is our lifestyle. Adopting a healthy lifestyle, and staying mentally and physically active may lower the risk or delay the onset of Alzheimer's. For example, approximately 30% of people with Alzheimer’s have heart disease and 29% have diabetes. Clinicians believe that managing these conditions can help reduce the risk. Indeed, the lead author of the GBD study said:

“While our study focused on the impact of expected trends in modifiable risk factors, other studies have suggested that up to 40% of all dementia cases could be prevented if risk factors were eliminated.”

You can do many things to reduce your risk of Alzheimer's today.

- Engage in aerobic exercise at least 30 minutes per day, five days per week.

- Eat a Mediterranean diet including olive oil, avocados, fruits, vegetables, nuts, beans, whole grains, fish and poultry. Avoid processed foods.

- Participate in social and cognitive activities.

- Get 7-8 hours of sleep, including deep REM sleep.

The importance of sleep is often overlooked. One study by Harvard found that people who slept fewer than five hours per night were twice as likely to develop dementia, and twice as likely to die, compared to those who slept six to eight hours per night. A second study found that consistently sleeping six hours or less was associated with a 30% increase in dementia risk compared to a normal sleep duration of seven hours. A third study found that better sleep not only reduced the likelihood of developing clinical Alzheimer's disease, but it also reduced the development of tangle pathology in the brain — another substance that accumulates in Alzheimer's disease.

It’s not just the quantity of sleep but the lack of quality sleep that can increase the risk of Alzheimer's: obstructive sleep apnea may increase risk by interfering with blood flow to the brain and normal patterns of brain activity that promote memory and attention. Similarly, the glymphatic system, which clears the brain of protein waste products, is mostly active during sleep. It helps the brain flush away harmful toxins and beta amyloid deposits that cluster and clump together to form Alzheimer's plaques.

Another modifiable lifestyle factor that contributes to the development of Alzheimer’s is smoking. It causes cellular inflammation and worsens several health factors that increase Alzheimer’s risk. These include heart diseases, obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia. How big is that increased risk?

- 79% higher risk = Current smokers versus Never smokers

- 70% higher risk = Current smokers versus Former smokers

- 21% higher risk = Former smokers versus Never smokers

Additionally, according to the World Health Organization, smokers have a 45% increased risk of developing dementia.

Risk Factor: Genetics

A family history of Alzheimer's may increase your risk of developing the disease. The degree of risk changes based on both the number of relatives you have with Alzheimer’s and how they are related to you. For example, you are estimated to be:

- 1.73x more likely to develop it if you have one first-degree relative (parent, sibling, or child) with Alzheimer’s

- 2x more likely to develop it if you have one first degree relative and one second degree relative (aunts, uncles, or grandparents) with Alzheimer’s

- 4x more likely to develop it if you have two first-degree relatives with Alzheimer’s

- 15x more likely if you have four first-degree relatives with Alzheimer’s

Per the National Institute on Aging, a family history of Alzheimer’s does not mean that a person will develop Alzheimer’s, and a lower risk does not mean a person won’t get it. Rather, a person’s family history can be a warning sign to help identify people who may benefit from monitoring for early disease symptoms and from adopting lifestyle interventions to decrease their risk.

In most cases, Alzheimer’s does not have a single genetic cause (monogenic). Instead, it can be influenced by multiple genes (polygenic) in combination with lifestyle and environmental exposures (multifactorial). A person may inherit some genes that can either increase or decrease the risk of Alzheimer’s.

The most well-known gene that influences Alzheimer’s risk is the apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene, which is involved in making a protein that carries cholesterol and other types of fat in the bloodstream. Everyone inherits one of three forms (alleles) of the APOE gene. You can inherit the e2, e3 or e4 allele from each parent, resulting in six possible APOE combinations: e2/e2, e2/e3, e2/e4, e3/e3, e3/e4 and e4/e4. The e3 allele is neutral, but if you are a carrier of the e4 allele, it increases your risk. In contrast, if you have the e2 allele, it may decrease your risk. Researchers believe that as many as 56-65% of people with Alzheimer’s have at least one copy of the APOE e4 allele whereas 11% have two copies of the e4 allele.

The 2023 report from the Alzheimer’s Association concluded that people who inherit one e4 allele have nearly 3x the risk of developing Alzheimer’s compared with those with two e3 alleles. Compounding that risk, those who inherit two e4 alleles have an estimated 8x-12x risk. Plus, those with the e4 allele may be more likely to develop beta-amyloid accumulation and Alzheimer’s disease at a younger age.

For those with early-onset Alzheimer’s, rare pathogenic variants in one of three genes can cause the disease:

- Amyloid precursor protein (APP) with 100% penetrance

- Presenilin 1 (PSEN1) with 100% penetrance

- Presenilin 2 (PSEN2) with 95% penetrance

According to the National Institute on Aging, a person who inherits a pathogenic variant in one of these genes has a “very strong probability of developing Alzheimer’s before age 65 and sometimes much earlier.” But, among those with early onset Alzheimer’s, only 10% to 15% can be attributed to variants in the APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2 genes. There is still much to understand about why some people have early-onset Alzheimer’s.

Most recently, in 2022 researchers published a study in Nature Genetics that reported 75 genes linked to an increased risk of Alzheimer’s – 33 of which were previously identified. Of the 42 newly associated genes, many relate to proteins in the body that govern how neuroinflammation and the immune system might damage brain cells.

For example, the study found that a number of genes were associated with an immune regulator called LUBAC, which activates genes and prevents cell death. Similarly, some of the newly discovered genes cause microglia to be less efficient. Microglia are the brain’s immune cells that are tasked with “taking out the trash” – clearing away damaged neurons. Thus, inefficient microglia may accelerate Alzheimer’s progression.

The study also identified several other genes that regulate inflammation, which is the body’s defense mechanism to kill off pathogens, but it also plays a role in removing damaged cells. Among the many genes related to neuroinflammation, the study found a cluster of genes associated with tumor necrosis factor alpha (“TNF”), which is made by the immune system to regulate inflammation.

Finally, another key insight of the study was that other neurodegenerative brain disorders such as Parkinson’s, frontotemporal dementia, Lewy body dementia and ALS may share some of the same underlying genetic basis as Alzheimer’s. Thus, the study’s authors opined that the data may exemplify a potential continuum between neurodegenerative diseases.

Risk Factor: Gender

In addition to genetics and lifestyle comorbidities mentioned above, gender also plays a role as approximately 2 in 3 people with Alzheimer’s are women. How significant is the risk? Once they reach 60, women have a 1 in 11 chance of developing breast cancer but a 1 in 6 chance of developing Alzheimer's disease. One reason for this increased gender risk: there are 5.7 million more older women than older men living in our society.

Besides age, the other leading risk factor for Alzheimer’s is a sex-linked gene: the APOE4 gene has a stronger influence on women than men. For example, women with APOE4 are more likely than men to have greater brain atrophy and lower brain metabolism, along with worse memory performance. They are also more likely to develop mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer's disease than men with the allele.

But age and genetics don't explain the whole story. Interestingly, because the risk of other forms of dementia does not vary by gender, this provided researchers with a clue as to the possible reason for the increased risk only in Alzheimer’s.

One hypothesis results from gender differences in our immune systems. Typically, the immune system is stronger in women than men. Harvard researchers hypothesize that the immune system may cause amyloid plaque to be deposited in the brain in order to fight off infections. Because women may have more amyloid plaque than men, this may predispose them to a greater risk of developing Alzheimer's disease.

The increased prevalence of Alzheimer’s among women may also result from changes in hormone levels. Recently, researchers at Scripps and MIT found a connection between estrogen and an inflammatory immune protein called complement C3. This harmful form of complement C3 exists in higher levels in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s.

"Complement proteins can trigger brain-resident immune cells called microglia to destroy synapses—the connection points through which neurons send signals to one another. Many researchers now suspect that this synapse-destroying mechanism at least partly underlies the Alzheimer’s disease process, and loss of synapses has been demonstrated to be a significant correlate of cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s brains."

Researchers showed that estrogen – which drops precipitously during menopause – normally protects against the creation of complement C3. But in post-mortem studies, complement C3 was present at much higher levels in the brains of women who had died of Alzheimer's. In fact, the levels of S-nitrosylated C3 (SNO-C3) were more than six-fold higher in female Alzheimer’s brains.

Risk Factor: Military Service

Military service can impact risk. A new study published in the Alzheimer’s & Dementia Journal in November 2023 suggested a slightly increased risk of Alzheimer’s in men who served in the military: 26% greater odds of having amyloid plaques and 10% greater odds of having neurofibrillary tangles made of abnormal tau proteins. But much more research is needed to establish a causal relationship and to determine possible associations with that risk.

Risk Factor: Race and Ethnicity

Alzheimer’s Disease disproportionately impacts people in underrepresented minority communities (“URM”) like Black and Hispanic Americans. While White Americans make up the majority of the 6.7 million people with Alzheimer’s disease, Hispanic Americans have a 1.5x higher risk and Black Americans have a 2x higher risk.

In addition to the higher risk, a higher proportion of Black and Hispanic Americans experience a diagnostic delay from symptom onset. The average delay for White Americans is 31 months, whereas it is 35 months for Black Americans and 44 months for Hispanic Americans. And according to this 2022 study, Black and Hispanic Americans are typically diagnosed in the later stages of dementia when they are more impaired, and need more medical care. Once diagnosed, the health disparities continue as they are less likely to receive – and more likely to discontinue – antidementia drugs. Moreover, after receiving a clinical diagnosis, people from URM are also less likely to receive follow-up care by dementia specialists (like cognitive neurologists and neuropsychologists). Ultimately, with this confluence of health disparities, people from URM communities with dementia also have higher hospital mortality rates.

Delays in Diagnosis and the Role of Primary Care Physicians

Dementia is underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed across the US population, not just in URM communities. These delays in diagnosis can exacerbate disability, reduce treatment effectiveness, impede timely care, and increase health care costs. In addition, people with undiagnosed dementia may be more likely to participate in activities that could cause harm to themselves or others, such as driving, preparing hot meals, managing finances and improperly taking medications.

One of the reasons for the delay in diagnosis is that many people do not discuss cognitive symptoms with their physicians, mistakenly confusing early symptoms of dementia with normal aging. As such, if you are noticing any changes in memory, mood or function in you or your loved ones, it’s critical that you raise these symptoms with your primary care physician and request a referral to a neurologist who specializes in dementia. If you don’t mention it, your physician may not notice the need for a cognitive assessment as 97%+ of PCPs wait for patients or family members to make them aware of symptoms.

Even when patients discuss their symptoms with their primary care physicians, a number of diagnostic barriers exist, such as the physician’s lack of familiarity with diagnostic criteria, insufficient time to evaluate symptoms and provide follow-up care, and an incorrect belief that there are no viable treatments to help with symptoms. The Alzheimer’s Association created this infographic about roadblocks to early diagnosis of Alzheimer's and dementia.

Unfortunately, there are not enough physicians who understand the nuances of dementia. For example, in this 2020 Alzheimer’s Impact Fact Sheet, more than half of primary care physicians (PCPs) reported that there were not enough specialists in their own geographic area to meet patient demand, which results in 8 in 10 PCPs handling the burden of dementia diagnosis and care. This creates an incongruity in patient care as nearly 1 in 4 PCPs had no residency training in dementia diagnosis and care. Even among those who did receive some training, 2 in 3 said the amount was “very little.”

The net impact of this lack of specialization? Even though PCPs make the majority of initial diagnoses, in a 2019 survey by the Alzheimer’s Association, nearly 40% of PCPs reported that they were “never” or “only sometimes” comfortable making a diagnosis. More than a quarter of PCPs reported being “never” or “only sometimes” comfortable answering patients’ questions, and 50% did not feel adequately prepared to care for people diagnosed with dementia.

This is why Synapticure is committed to work with PCPs around the country to support their patients’ dementia care. Because of our telehealth platform, we can see patients in all geographic regions, including those in rural and underserved communities. Our patient-centric dementia care model includes:

- Monthly check-in appointments with the patient’s own care coordinator

- Prompt appointments with dementia experts including cognitive neurologists, behavioral health experts and neuropsychologists

- At-home physical, occupational, speech and respiratory therapy

- Medication and symptom management

- Coordinating durable medical equipment

- Counseling about clinical trial options

- Insurance navigation support, explaining available SSDI, Medicare, Medicaid, Veteran’s benefits, commercial insurance plans and supplements, and long-term care policies

- Genetic testing from home coupled with pre- and post-test counseling by our own genetic counselors (including pre-symptomatic and anonymous testing)

Conclusion

If you want to learn more, Synapticure hosted a webinar with some members of our dementia care team to discuss the types, stages and symptoms of dementia.

If you or your family members are interested in learning how you can receive dementia care from the comfort of home, you can schedule a free consultation with one of our care coordinators by clicking this link or calling (855) 255-5917. We would be honored to help you and your loved ones who are dealing with dementia.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Ben Williams, MD, PhD is a leader in Synapticure’s cognitive practice. Prior to joining Synapticure, Dr. Williams worked as a neurologist for decades, specializing in treating people with Alzheimer’s and various forms of dementia both in general practice and at multiple ADRCs. He did his neurology residency training at UCSD under Dr. Robert Katzman, who was the doctor that identified Alzheimer disease as the primary cause of dementia in the elderly. Later Dr. Williams returned to Texas, where he worked with another early Alzheimer’s leader, Dr. Roger Rosenberg. Most recently, Dr. Williams worked at the new ADRC that was developed at Wake Forest Medical School. Dr. Williams has been board certified in Behavioral Neurology and Neuropsychology by UCNS since 2012.